Hotter than (Sa)hel

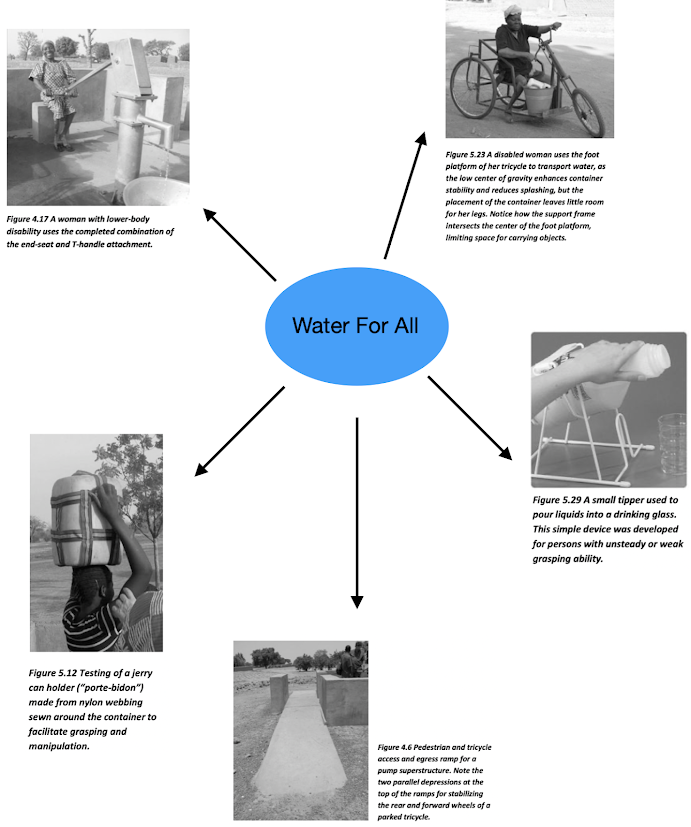

As my blog draws to a close, I want to finish on a heated issue: the instability of the Sahel region. Home to Lake Chad - a transboundary freshwater source - the area has become a locus for intersecting challenges of climate change. Temperatures in the Sahel are rising 1.5 times faster than the global average, depleting natural resources at a rate that outstrips demand. Since the 1960s, Lake Chad has shrunk by 90% - a figure that equates to approximately 24,500km² ( Figure 1) . Yet the livelihoods of 30 million people within Nigeria, Chad, Niger and Cameroon still depend upon it. For an area that is already characterised by poor governance, a persistent economic crisis and a bourgeoning terrorist organisati on ( Boko Haram ), this does not bode well. In fact, it only exacerbates existing crises , creating conflicts that have a gendered impact. This brings me to the topic of my final blog on water and gender: climate-related challenges for indigenous women in the Sahel. Figure 1...