Making visible the "invisible"

Today marks 'International Disability Day', bringing the rights and needs of disabled persons to the forefront of society. In an effort to contribute, this week's blog is dedicated to the relationship between disabled people and water within Africa.

In March 2010, ‘Water, Sanitation and Disability in Rural West Africa’ was published. This report looks into the lives of 260 disabled people living in rural Mali, highlighting the significant barriers that are faced when collecting and using water. However, over 11 years have passed since the publication and disabled persons remain a largely excluded group from both society and policies. Confined to their homes as a result of stigmatisation and poor resources, disabled people have been termed the “hidden poor”. This post aims to make visible the “invisible”.

Across rural West Africa, disabled people are the most isolated and vulnerable members of communities. Born out of a fear that disability spreads, many disabled persons are excluded from collecting water. In circumstances where they do, this gendered task presents multiple challenges. Their marginalisation manifests through exclusion from project planning and implementation of water facilities. In turn, this reinforces their ‘invisibility’.

In particular, disabled women are impacted by social stigmas. They live in a society where gendered stereotypes dictate their time-space activities, making water collection the inherent role of the female. Conversely, a sense of self worth is derived from these household tasks. Therefore, being unable to collect and use water demoralises disabled women.

Social biases also weaken the power of disabled females. Family and community members argue that water collection shouldn’t be carried out due to “risk of personal injury”, which could lead to further social exclusion and gender-based violence. However, most disabled female participants disagreed and felt that the decision should be their own, not that of others’. Evidently, there is a lack of agency and space given to disabled persons within the water sector.

One 17 year-old blind woman disclosed that she “sneaks out at night, against her parents’ wishes, to practice drawing and carrying water in the hope of one day fulfilling the roles of a married woman and mother”. The complexities of being a disabled female with gendered expectations is brutal, urging development policies to recognise the intersections of 'women'.

Physical Obstacles

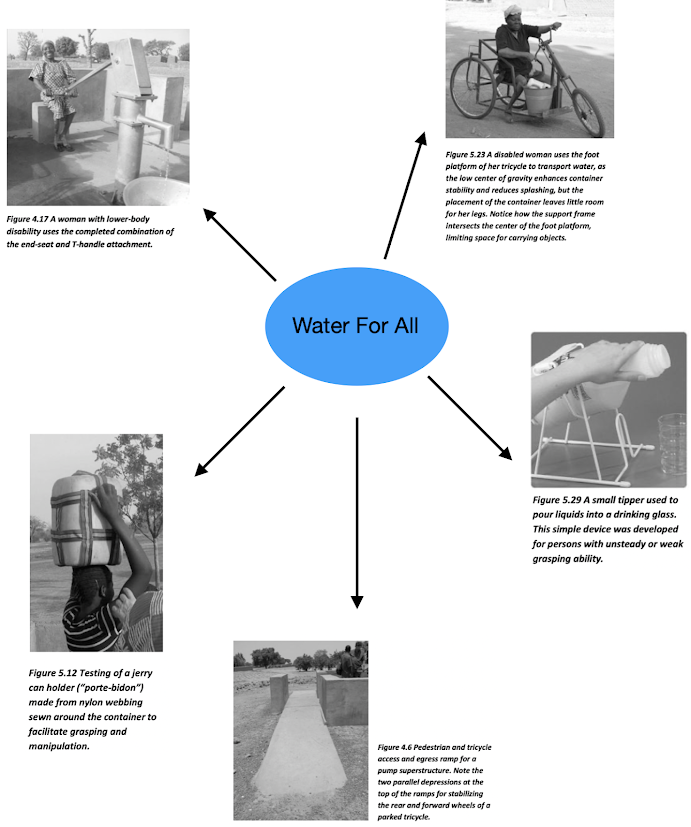

- Due to water inaccessibility, those with lower-body limitations are forced to crawl or drag themselves to water points.

- For the 95% of disabled participants who collect water from an open well, the mud and water surrounding these wells presents a slippery surface which the person struggles to find stability on.

- For water pumps, the handles are difficult or altogether impossible for those persons with weak upper body strength. Within the study, only 6% could use hand-pumps themselves.

- Transportation of water presents another challenge; common problem is the spillage of water. Consequently, many avoid fetching large volumes, filling their 25L containers with only 10-15L. This results in an increase in daily trips: approximately 4 times for disabled people, in comparison to the 1-2 trips for able-bodied people.

- Further limitations involve the use of water: struggling to pour it into cups for drinking and cooking; unable to bend over and wash clothes; incapable of bathing themselves.

Financial Barriers

- In some instances, disabled persons pay someone else to collect and carry water. However, due to their social status, it is extremely rare that someone would do this for a disabled woman. Additionally, this is only possible for households that could afford such a transaction.

- Disabled persons often can't afford the resources, such as tricycles and carts, to aid the process of water collection.

Inaccessibility or inclusivity?

Hey Ellie, thank you for this meaningful post on the International Disability Day. Your discussion about disabled women and their roles in providing water for the households really points out a hard truth that is often neglected in many discussions on this topic. It has also reminded me about the concept of "double consciousness" - in this case, being women and disabled persons. At the end, you briefly touched on some solutions, and I wonder if there are some research focus on the effectiveness of these solutions, and how do the women feel about the solutions?

ReplyDeleteThank you for reading my post! And for your thoughtful comment!

ReplyDeleteI have looked into the effectiveness of solutions and I can't find any evidence for this specific report in Mali. In fact, most studies fail to carry out regular progress reviews to ensure the satisfaction of those whom they're directed at.

However, a report by WaterAid, (which implemented adaptions for disabled persons across many locations) did carry out such reviews. One issue that came up - and should be a warning for future projects on disability within the water sector - is that implementations were discussed with disabled persons only, rather than with the whole community. Whilst this is needed, in order to raise the voices of people with disabilities, it also legitimises their isolation from the rest of society. Instead, the report emphasis that whole community projects need to be carried out.

Additionally, it mentioned the lack of governmental support and funding. Whilst localised projects are extremely important, we must not forget about the wider systems and structures which need to be reformed, as these often underpin large-scale taboos. Without radical change, the localised effects will not be enough.

Here is the link if you wanted to check it out! https://wedcknowledge.lboro.ac.uk/resources/learning/EI_WASH_ageing_disability_report.pdf